Have you ever heard someone say that affordable housing costs too much to build? It’s hard to justify that statement unless we first compare the cost of affordable housing to the cost of private market-rate housing. Until now, we’ve never had public data on the latter, but recently, the Terner Center at UC Berkeley published Making It Pencil: the Math Behind Housing Development – 2023 Update, which includes pro forma analyses for prototype mid-rise market-rate rental housing developments in four California markets: Uptown/Downtown Oakland; San José/Santa Clara; Downtown/Midtown Sacramento; and the Westside of Los Angeles.

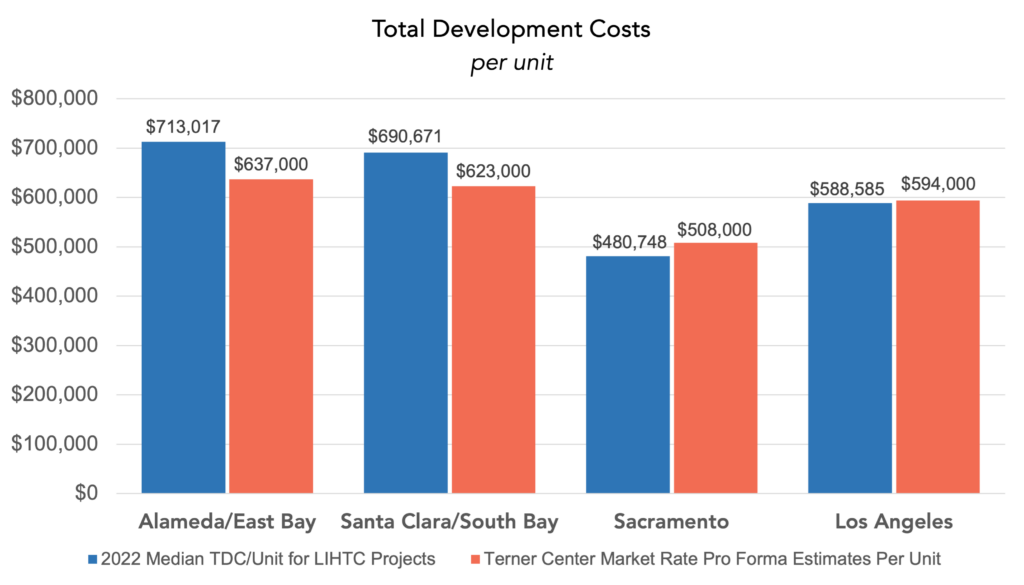

The California Housing Partnership has compared the costs of these market-rate prototypes with the median cost of developing affordable rental homes, which we track, in those same counties. It turns out that costs are generally comparable, and in fact, affordable housing is less expensive than market-rate housing in the Sacramento and West Los Angeles markets.

What makes this data even more surprising is that affordable housing does incur some costs that market-rate developments do not. First, affordable housing developers spend years cobbling together disjointed and unaligned public financing sources. The Partnership’s analysis shows this adds $47,400 in cost per unit on average.

Second, many affordable housing developments are required to pay construction workers union-level prevailing wages, which market-rate developers generally avoid doing, leading to significantly higher labor costs for affordable housing. While there are important social benefits to paying construction workers prevailing wages, a 2019 study by the Terner Center at UC Berkeley found that prevailing wages increased development costs per unit by 13.4%.

Third, because low rents in affordable housing limit an owner’s return, state programs allow affordable housing developers to earn a limited up-front developer fee to compensate them for their costs and risk, and this fee is added to the cost of development.

In other words, under an apples-to-apples comparison that excludes these three unavoidable elements, affordable housing would fare even better when comparing costs to market-rate development.

So the real issue for California is not that affordable housing is more expensive but that developing housing of any type, affordable or market-rate, is expensive by national standards.

In the last few years, state leaders have greatly streamlined the process of getting land use approvals from local governments to build housing and reduced litigation risks. This will help.

However, much work remains to be done to address development impact fees assessed by local jurisdictions desperate to offset the rising cost of public infrastructure as well as the meteoric rise in the costs of insurance.

High material and labor costs in California continue to be a major constraint on residential development that government has not found a way to address. While modular housing production has shown some promising results, it has yet to consistently and significantly lower these costs.

With respect to the disjointed and unaligned public financing process mentioned above, the state can and must streamline the process so that developers may obtain all the state resources they need at one time with a single application thereby reducing costs by nearly $50,000 per door. The state can also help developers save on average $1 million per development on interest costs by disbursing its loans during the construction period and by capping monitoring fees at the level needed to cover actual costs.

Even with costs as they are, it is important to remember that the state funds on average less than 20% of costs to develop affordable rental housing and that these investments provide benefit for 55 years, such that it costs the state only $631 per person per year to house a low-income person, a good investment by any definition. This equation will improve with each step the state takes towards reducing the costs described above.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Stivers leads the Partnership’s legislative and regulatory advocacy efforts. He was previously acting Deputy Director for the Division of Financial Assistance at the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) where he oversaw more than 20 loan and grant programs. Prior to HCD, he was the Executive Director of the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (CTCAC), responsible for the administration of the California’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program.